Welcome to the City of New Berlin, Texas

The citizens of this small city welcome you to New Berlin, a city that cherishes its German heritage and strives to keep those traditions alive along with those of all immigrant descendants. While in New Berlin, enjoy the peaceful serenity of this small, rural village.

We have digital copies of all city ordinances, meeting agendas, minutes and special items found in the Government tab on this site. You may also acquire copies of these items by calling or visiting New Berlin City Hall (830) 914-2455. Notices will continue to be published on the bulletin board outside at City Hall and, when required, in the Seguin Gazette newspaper.

The city is governed by a mayor and five council members.

City Council meets on the third Monday of each month at 6:30 PM at the City Hall.

Planning & Zoning meets on the first Monday of each month at 7:00 PM at the City Hall.

Meeting Agendas

MARCH 2026

PLANNING AND ZONING REGULAR MEETING CANCELLED: MARCH 02, 2026: CANCELLED AGENDA

CITY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING: MARCH 16, 2026: AGENDA

Traffic Activity Report

Community

The Citizens of this small city welcome you to New Berlin, a city that cherishes its German heritage and strives to keep those traditions alive along with those of all immigrant descendants. While in New Berlin, enjoy the peaceful serenity of this rural village.

Wilkommen New Berlin!

Welcome to the New Berlin Community Club, a volunteer organization of individuals who meet regularly for fun, fellowship, and community support.

The Community Club owns and maintains the Community Center in the City of New Berlin. The Club meets on the third Friday of every month at 7:30 P.M. For information on renting and using the Community Center, contact Tammy Mills at 830-660-0270.

Have you ever thought of applying for a Texas Historical Cemetery marker for your family cemetery, but you just didn’t know quite how to get started? Getting started is probably the most difficult part. Once you begin, you’ll find that it really isn’t that difficult. The Texas Historical Commission provides a guide that clearly states the criterion for designation and tells how to write the application.

Applying for a Texas Historical Cemetery marker for a family cemetery can be a very rewarding and fulfilling experience. It is rewarding, in that it requires some basic research of your family history. In the process, you may make interesting discoveries about your ancestors. Who were your family members who immigrated to this country? Where did they come from? Why and when did they come? What were their occupations? What were their hobbies, interests, educational backgrounds and religions? It is fulfilling, in that once you have reached your goal and received the marker, you realize that you have honored your ancestors in a very special way. Marking their final resting place as a Texas Historic Cemetery acknowledges the role they played in the history of the state of Texas. It acknowledges the sacrifices they made and hardships they endured to ensure a better way of life for themselves and their descendants.

How do you get started? If you are thinking of applying for a marker for a cemetery in the New Berlin area, call Janie Wallace at 420-3771. Janie and her sister, Vivian McKee, recently applied for cemetery marker for their family cemetery, were successful and would be willing and able to walk you through the process. You may also contact Mr. John Gesick, Chairman of the Guadalupe County Historical Commission for information. He may be reached at 830-379-6717. Another resource is the Texas Historical Commission at P.O. Box 12276, Austin, TX 78711-2276. To reach them by phone, call 512-463-6100. They will be happy to send you their packet of materials explaining the process and will answer any questions you might have.

Two basic criterion govern the approval for the Historic Texas Cemetery designation: (1) the cemetery must be at least 50 years old, and (2) deemed worthy of preservation for its historic associations. You will need to write a brief narrative history that relates its significance to the local area and provide documentation to establish its boundaries. Establishment of boundaries can be achieved very simply by obtaining a map from the County Tax Appraisal District Office. You will also have to provide black and white photographs of the cemetery.

In researching your ancestry, many resources and records are available. The Dittlinger Library in New Braunfels has many volumes of passenger ship’s lists. They contain the names and ages of all passengers, where they were from, their destinations, their dates of departure and arrival and their dates of departure and arrival and their occupations. That is an interesting place to start. Other sources of information are land records, census records, church records, citizenship papers, will probates, birth and death records, marriage records, funeral home records, obituaries, newspapers and cemeteries,

Cemeteries are among the most valuable of historic resources. Names on grave markers serve as a directory of early residents and provide insight into the unique population of an area. Tombstone marker designs and cemetery landscaping exemplify cultural influences that helped shape the history of Texas.

New Berlin has numerous family cemeteries. We believe the following list is comprehensive, but are always eager for information we may have missed: Hoese, Warncke, Doege, Schultze, Linne, Hoffman, Schmidt, Boecker, Beutnagel, and two unmarked cemeteries on separate properties. Ideally, we hope to obtain a marker for each of these cemeteries. This, of course, requires community involvement. An interested person from each family would have to clear the project with the family, write the narrative and provide the documentation for the application. The New Berlin Historical Society would be happy to assist in any aspect of the project.

Cemeteries help to define the character of a community, and marking them as Texas Historic Cemeteries will give a strong sense of history to the community. People are more likely to protect and maintain these cemeteries when they realize their significance. The Texas Historic Cemetery marker is a positive way to reaffirm the fact that these places are sacred ground and are treasured by the community.

If you would like more information about obtaining a Texas Historic Cemetery marker for a cemetery in the New Berlin area, please contact the New Berlin Historical Society. Call Janie Wallace at 830-420-3771 or Vivian McKee at 830-303-1305.

Contributed by the New Berlin Historical Society.

At seven o’clock on any given morning in New Berlin, I can tell you with reasonable certainty who is sitting up at Brietzke Station having coffee and exaggerating about rainfall, cattle prices, and how much their crops are or are not growing. Seven o’clock is the first shift: Bob Seward, Billy Shultze, Willie Esparza, Browns, Zuehls, Mr. K, Mike and I, and sometimes Frank Howell and Diana. Shortly thereafter, begins a steady flow of school kids, whose parents drop them off to wait for the bus at the Station. Mutsie has been putting local kids on the bus since the Station opened in 1977. Eight o’clock brings the second shift of coffee drinkers: Jim Lewis, Elsie Zuehl, Lula Mae Summers, Mr. and Mrs. Fowler (the honey people) and Dennis. Pinkie Faylor used to come in about 8:30. Pinkie always told the very best jokes.

If a regular isn’t there, they are either sick or dead. You get a “bottomless cup” of coffee for sixty-five cents. That’s a small town perk. If you want breakfast, you can get it. If not, you can just catch up on the news and visit.

There is a rhythm to the place, and that is comforting. Every day of the week has its own lunch special, and they don’t vary from week to week. Chicken and dumplings is my favorite. Mutsie makes the rolled out kind. She cooks like a mom who can really cook. You can get it to go, or eat in, or call in an order and pick it up. She calls a lot of us honey, and she means it. She knows the news first, knows who to call for every conceivable kind of rural emergency and will help you with anything. She is treasured out here.

Brietzke Station is an institution in New Berlin. If you say you’re from New Berlin, people say, “Oh, you have that little café out there, Brietzke’s.” It is currently famous for the fish specials on Wednesday and Friday nights. Big John and Mutsie Bohannon have owned and operated the Station since 1977. I’ve been going in there practically every day since August of 1987, when we bought the Tewes house in New Berlin and began restoring it.

The building that houses what is currently the café has a long and varied history. It has been several things, but it has always been of central importance to this small community. In all of its various incarnations, it has always been a gathering place. The owners have always been sociable sorts and have not objected to the locals hanging around. If you are old enough, you might remember what the building used to be—if not, here is the story.

In January of 1918, Arthur Schubert purchased two acres of land in the village of New Berlin from Otto J. Muelder. The property stood on Marion-LaVernia Road, right next to the Muelder Store, Cotton Gin, and Saloon. It was on this land that Mr. Schubert built his house and then the structure that is now Brietzke Station. The original structure was about 32 feet wide and 48 feet long. Big John says that in Mr. Schubert’s day, it was a Ford dealership. He sold both Model-T and Model-A Fords. In those days, the locals played cards and dominoes and drank beer. The Schuberts had two children, Vernon and Stella.

According to Big John, if you go into the building today, the front portion, which is regular tile, is where the showroom used to be. The back portion, which has D’Hanis tile, is where the old garage was. For many years, it had a dirt floor and was where they did repair work.

Schubert sold the property to Walter and Edith Brietzke in August of 1939. Walter and Edith ran the place as a gas station and garage. Walter sold batteries and tires in the front of the building. He used the back half of the building as a garage. He also fixed tires. It continued to be a gathering place for the community, and on any given day you could still find between five and ten men, sitting around playing cards or dominoes and drinking beer. During Walter and Edith’s day, the locals who were most frequently present were Ben Stein, Leonard Bohannon, Alvin Pape, Walter Mattke, Charlie Koepp, and Mr. Bolton. Later, people gathered to watch TV, especially wrestling and special sports events. Big John vividly remembers the community gathering to watch the Max Spelling and Joe Lewis fight. People gathered just to spend time together. Joyce Young told me she met her husband, Harold, there.

Johnnie is Edith Brietzke’s brother. He lived with his sister for several of his school years. He says his brother-in-law, Walter Brietzke, was a fine man—one of the best. John was with him when he died on June 3, 1974, on his 70th birthday. His last words were the Lord’s Prayer—in German. Edith continued to run the Station until 1974. She sold a little beer, some gas and soft drinks.

In January 1975, Johnnie and Evangeline (Mutsie) Bohannon bought Brietzke Station from Edith. The move to New Berlin from San Antonio did not bring John and Mutsie to unfamiliar ground. Johnnie and Mutsie grew up in New Berlin. His family moved to the area before his birth in 1926. They were the only Irish family in the area. His parents were sharecroppers on the Baldwin land. They farmed 120 acres and grew “whatever they could grow and make a dime on.” His home place still stands on FM775. Mutsie was a Radtke; her family lived on Santa Clara Road. She went to school in New Berlin until she was about eight years old. Then her family moved to Karnes County. Roger Weyel was in her first-grade class. (Roger sometimes comes to the café looking for chocolate pie.)

Mutsie and Johnnie were married in LaVernia on November 8, 1945. Otto and Josephine Radtke stood up for them. Afterward, they went to Mutsie’s mama’s house and had a turkey dinner. Then the neighbors gave them a chivaree. (Mutsie had to tell me what that was.) The gist of it is that neighbors descend upon your house after your wedding and make a lot of noise. The family serves refreshments and everyone congratulates the couple. It is a way of acknowledging the marriage. They spent the years when their kids were growing up, in San Antonio. Johnnie worked at Butter Crust Bakery and Mutsie raised kids and later worked at the courthouse. They built their house in New Berlin in 1975 and renovated the Station in 1976.

Not all predictions about the prospects for a restaurant in New Berlin were rosy. Mustie’s Uncle Otto Radtke told Big John, “You’re crazy. You won’t sell six hamburgers a week out here.” To the surprise of many, when the business opened its doors in early 1977, it was an immediate success.

It remains so today, twenty-five years later. Johnnie says the reason for their success is quality, service and a fair price. All that is true, but it is also that the place holds over 75 years of memories. People remember being children here. They met here and married and brought their own kids back to this place. There is comfort in places that remain. Stepping through the door is like stepping into your own past, as well as a shared community past. People remember stories of the Schuberts and Walter and Edith Brietzke and Mutsie and Johnnie. Today, the food is “mom food,” ever comforting, and the people are familiar. And there is always Mutsie. After all these years, I’m sure Johnnie knows she is the real secret to his success.

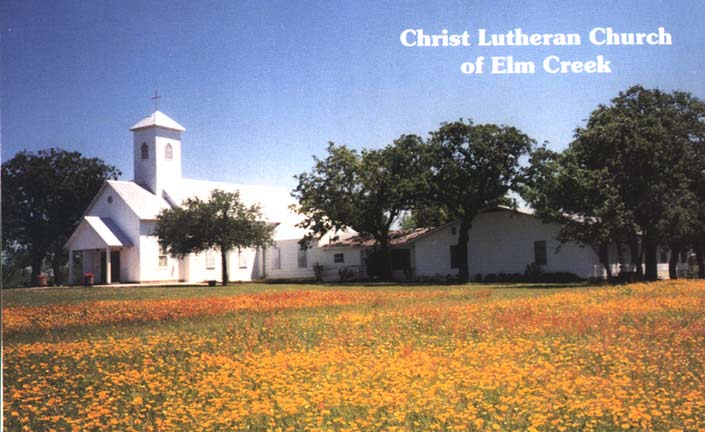

Christ Lutheran Church, which was founded February 14.1886, played an important role in the life of many New Berlin residents in the early days of this Community.

In the year 2000, a new steeple was placed on the 114 year old building. In the 115 years of service to their Lord, these faithful people have persevered. Many, many, baptisms, confirmations, marriages and deaths have been recorded in the historic archives of this congregation. They continue to give thanks to their Lord for giving them the faith and courage to persevere despite the unusual hardship that marked their beginnings

The early settlers were determined to have a church and persevered despite setbacks that would have daunted less determined souls. They actually built three separate churches on the same site in under a year. The first and second were destroyed, but the third still stands today. The story of the early congregation is one of devotion and determination. Mr. and Mrs. August Lenz donated four acres of land for the church and cemetery. On May 2.1886 the first church building was dedicated. This building collapsed in June of 1886 when it was struck by lightning during a storm. Another building was built, only to be destroyed in August of 1886 when a great hurricane passed through this area. This storm was so furious that it completely inundated the port city of Indianola before lashing its destructive forces across central Texas. Indianola was never again rebuilt. Many immigrants of this area had entered the United Stated at this port city.

What other destruction and damage did this hurricane cause? Were their homes and barns blown away? This destruction occurred in August; harvest time for these farmers. Did they lose their corn, cotton, peanut, and hay crops? Did they lose the fruits and vegetables in their gardens? How many cattle, horses, mules, chickens and turkey did they lose to the floods that usually accompany a hurricane? How much time did they have to prepare for this storm? Not much, as communication was practically nil! How brave and dedicated to their Christian faith they must have been! How was it that they did not become discouraged and give up, thinking that God had abandoned them? This clearly shows us the fortitude, determination, true strength of character and faith these immigrants had. They trusted and believed that their God would see them through these trials and tribulations.

The third church was built and dedicated in February of 1887. This building is still used today as the sanctuary and main worship center for the congregation. In time, a parsonage was built for their pastor and the congregation grew.

Many descendants of the charter members of this courageous and faithful congregation are residents of the area today. Among family names of the charter members are. Lenz, Mattke, Koepp, Helmke, Radtke, Schievelbein, Schulttze, Warncke, Markgraf, Hartmann, Helnke, Schraub, and others. The donors of the property, Mr. & Mrs. Lenz, were the grandparents of Annie Lenz Penshorn and the great-grandparents of Jimmie Penshorn and Marlene Warncke Young, among others.

Church records provide a snapshot of the time period. During the year that the church was being built, three separate times, life went on with its usual joys and sorrows. According to the church records, there were two weddings in the parish in 1886. Wilhelm Kunde was married to Maria Stolze and Heinrich Wieters was married to Maria Luedemann. Those members who died in 1886 were Carl Schievelbein and four children whose parents were Friederick and Wilhelmine Lenz Koepp. The children were Wilhelm, age 20; Wilhelmine, age 16; Dorothea, age 12; and Ida, age 3. They died from February 16 to February 24 of an epidemic believed to have been diphtheria. One child survived, Adella, age 10. How utterly catastrophic!

We can only vaguely imagine how devastated the dedicated faithful members of this congregation, located in the total wilderness, could have felt. The congregation was located 12 miles from Seguin, only a small community itself in 1886. La Vernia and Marion were also just barely settlements. New Berlin was totally isolated from a town of any size. How wonderful they must have felt to finally have achieved their goal – a church in which to worship!

(Some of the members of this congregation bad been attending church in New Braunfels or Seguin prior to this time.) This building was built at great sacrifice. The members were immigrants, struggling simply to survive, growing the food they needed to eat and building a structure to escape the winter’s harsh cold and the summer’s severe heat. Most of them were farmers and surviving on a farm was not easy. When they arrived, land had to be cleared, wells dug, houses and barns built, and endless list of tasks had to he completed. They had to contend with disease, starvation and loneliness, as they had left their families and friends in the old country.

In the face of these monumental tasks, the construction of a church was still of paramount importance to the German Lutheran families of New Berlin. Despite the unfathomable setbacks of the first year of Christ Lutheran Church, they persevered, building their sanctuary three times. It stands today as a testament to their devotion and determination.

The Jaenke Family’s trip from Germany to America in 1888

by Elisa jaenke Albrecht written 50 years later. Translated by Nola Schroeder Ristow – 1991

In the year 1888 the 2nd of December, the Jaenke family left their home in Vangerin, Germany, early in the morning while it was still dark. Father Karl, Mutter Bertha, Wilhelm, Emilie, Elise, Juluies, Albertina, Rosalina, and Franz Jaenke gathered on the train yard at Vangerin and drove off to Stetten and went by Berlin. At Stetten the train took water, and we drove on to Brehmen. A hotel servant from the hotel got us, and we waited there until the 5th of December. There with us was also another family, and more young single people, traveling off.

On the morning of the 5th of December, we left Brehmen, and after an hour the train brought us to Brehmerhafen. There was much to see. There was ship after ship with their masts and sails, something we had never seen. At the harbor, life was very busy and noisy.

And we children were naturally afraid and worried, and we held tight to our mother’s skirt so we would be sure to get on the ship. The loading and getting on the ship took a couple of hours. Shortly before noon, the ship (named ‘Amerika”) took off from the harbor. Everyone’s eyes were wet as we watched the old homeland grow smaller and finally disappear.

The trip to the sea was not very nice. There was much fog, so you could not see much. The ship blew the foghorn from time to time, and it was not nice to hear, but it had to be so ships did not run into each other. We were on the high seas when the storm started. We often thought that the ship would not straighten up again, it rolled to the side so our baggage rolled from one side to the other. So it went mostly day and night. And do not forget the sea sickness. Mother was so sick, she was in bed most of the trip. We all were sick, some were more sick than others.

The food was not so good, but you had to be satisfied with what you got. It was not an everyday feast. When at noon, it was pea soup or potatoes and herring, so it tasted good. There was some food that we could not eat. The bread looked so good, but it had a taste that we could not stand. With the butter, it was the same. At night, for supper, it was tea, that tasted like hay, but we did not go hungry. Brother Wilhelm was in good with the ships’ cook. Wilhelm sometimes helped the cook, so he got us other food that was good for us, and we were very thankful. Especially our dear mother, who at most meal times, sometimes could not eat at all. For the small children, there was milk and oats mush. Drink water we had to be careful with the. We did not go thirsty. We did not waste water. We had enough water because we were careful. We also had coffee that tasted like a dose of Epsom salts.

The last day on the ship was very nice. The weather was nice and the passengers had all gotten to know each other. Everybody exchanged addresses but I believe no one ever wrote to us and we didn’t write to anyone either. Everyone was going off in different directions.

When we were yet a few days from America, came the harbor pilot on board of our ship to steer our ship into the harbor of Baltimore.

It was with great happiness and joy when we heard that the coast of America was beside the ship. Everyone rushed on the deck to see the new homeland. That was a happy moment.

As the ship landed, it was early morning in the dark. The lights from Baltimore were still burning. It looked like a big burning Christmas tree. It was a pretty moment. So we arrived with God’s help. The unloading of the ship began as soon as it was daylight.

It was the 22nd of December and everyone was glad to have solid ground under their feet again. Now started the checking of baggage. That was soon over.

Now came the trains. One family went in this one and others in that one until all passengers were taken care of.

The first night in the new homeland was spent on the train. On the train, we were together with another family that we knew, but they soon went off in a different direction. Then we were alone but for a man from the ship. He had already been to America a few times. The trip on the American train was very interesting. We saw so much. The Cities that we came through. their names I have forgotten. There were so many and after 50 years I have forgotten some.

Sunday morning we came through Cincinnati, a nice city, in glorious sunshine. From there we drove to St Louis, and from there it was the beginning of Texas. After that, we came to Dennison on the 25th of December, in the morning, under heavy rain. There we had to wait a long time for our train. At last, the train came. The next morning we were in Houston. There we were told that in the afternoon by 4 o’clock we could arrive in Marion. Our happiness was great to be so close to Zuehl, but that seemed to us the longest part of our trip. Finally, we were in Marion. Our baggage was already there at the depot.

As we stepped off, there were two men there. A young man came over and spoke to us, and asked if we were the Jaenke family, this of course we were. This young man was Wilhelm Zuehl, then a young man 50 years younger than today.

There was no one else there to meet us. Mr Zuehl then rode to his brother, Karl Zuchl, who was 2 miles from Marion and came back with a big wagon and 4 mules.

It was mud weather and the road was then no better at Marion than today, (written in 1938). He helped us with our baggage. When we got to his house, it was dark as we arrived. Mrs. Zuehl welcomed us heartily and had us stay overnight, for this hospitality we were very thankful. That was the first night at our new home.

Next morning came our brother-in-law, Karl Schroeder. He had been notified the night before of our arrival. He took us to his house near the small town, today named “Zuehl’. There we had a happy meeting, that to someone who has never experienced it, we could not describe.

Our sister Wilhelmina, the Mrs. Schroeder, had come over in the year 1883 with the Karl Fritz family. So this was the first time after long years to see her again. Sister Wilhelmina, in the year 1884 in November, had our sister, Bertha, come over. So we soon had another very happy get-together.

So with much trouble and hardship. we came to our new home. We have our sister and brother-in-law Schroeder to thank. They helped us with the necessary things we needed for our trip and with many other things.

Dear listeners, today after 50 years we think with love of our old home, but our hearts are with our new home. So we had trouble and suffering to go through, but we lived. Dear listeners, so we must, at last, one more time, think of our old home with love. But everyone has so far come through all this alright. No one has been sorry that they left the old home, and settled in a new land. We live today in our beloved new land, our way. Yes, so in this country, now 3 generations have been burned. So let us be true to our new home.

The descendants of the Jaenke family are numerous In New Berlin and the surrounding towns. One of our favorite residents, who is now living at Rosewood Nursing Home in Universal City, is Helna Zunker Bielke. She was born in Aug 1912 near Leisner School. Her mother was Emilie Jaenke Zunker, who is one of the children in the history of the trip to the new home in America. Helna married Edwin Bielke in 1937 and they remained and farmed in the New Berlin area their entire married life. They had three children: Lee Jay, Charles Wayne, and Darlene Bielke Busby.

The Muelders in New Berlin

When my father, Herman George Muelder, died in Seguin on Wednesday, August 23, 1995, he left behind H. G. Muelder General Merchandising Store, the last remnant of a family business begun almost one hundred years earlier by his father, Otto J. Muelder and his business partners Luedger Kuehler and H. E. Kalies. These men, on June 6, 1898, had agreed “to associate themselves in a general partnership for carrying on, in the town of New Berlin in Guadalupe County, Texas, a general merchandise business and the buying and selling of cotton under the firm name of L. Kuehler and Company.” Under the terms of the agreement, Kuehler had obligated himself to furnish ten thousand dollars; Muelder and Kalies agreed to “donate their individual time and attention to the management and conduct of said business.” On July 25, 1916, Luedger and Hulda Kuehler sold the store, gin and seed house, saloon, residence, and barns and outhouses, to O.J. Muelder.

Descended from Derf Mulder and Justian George Mulder of Schuettorf, Hanover, Germany, both Lutheran ministers, Otto John Muelder married Blanche Schmidt at the Schmidt home in Kingsbury in 1897. A daughter, Irma, was born on October 3, 1898, and a son, Herman George, on October 2, 1909. The prominence of the Muelder family in the New Berlin area can be illustrated by newspaper accounts of the wedding of Irma to Edgar Weyel in September of 1917. The ceremony and reception were held at the Muelder home, with 200 guests in attendance. Piano, violin and clarinet played the wedding march as the bride entered the room, wearing a diamond lavalier, a gift from the groom. Toasts were offered by local dignitaries, including Mr. L. Kuehler, Reverend Freuh, and Judge Williams. The Marion Brass Band played during the reception, and Edgar Zuehl drove the newlyweds to San Antonio in his new Buick for their honeymoon. After their honeymoon, the couple took up residence in the Muelder home. Irma helped her parents with the business while her husband Edgar commuted to Marion where he had a car dealership. Two children were born to them in the house, Marjorie and Rodger.

Eleven years younger than Irma, little George (or “Bubie,” as he was nicknamed, looked up to her almost as another mother. Like most of the other residents of New Berlin at that time, he spoke German as his first language, not learning English until he started school. Growing up in New Berlin, as my father described it to me, included adventure and excitement as well as hard work and strict religious observance. Baptised into the Lutheran faith in January 1910, he was expected to observe Sundays in traditional form: go to church in the morning, wear your church clothes all day, be solemn, sit up straight, read only the Bible, pray and sing hymns, etc. No running, playing, shouting, or anything else that would appeal to a young boy was allowed. (He came to regard Sundays in much the same manner he regarded the orange juice with which his mother mixed his castor oil. No small wonder that, as an adult with a choice, although he had deeply ingrained religious values and beliefs, he chose not to attend church until he had a child of his own who he was afraid was going to grow up a little “heathen.” He and Mother, whose family was Presbyterian, compromised: they became Episcopalians. It was a choice both of them were happy with, except that when it came time to repeat the words in the Nicene Creed, “I believe in the holy catholic church…,” my good Lutheran father just kept his mouth shut!)

Eleven years younger than Irma, little George (or “Bubie,” as he was nicknamed, looked up to her almost as another mother. Like most of the other residents of New Berlin at that time, he spoke German as his first language, not learning English until he started school. Growing up in New Berlin, as my father described it to me, included adventure and excitement as well as hard work and strict religious observance. Baptised into the Lutheran faith in January 1910, he was expected to observe Sundays in traditional form: go to church in the morning, wear your church clothes all day, be solemn, sit up straight, read only the Bible, pray and sing hymns, etc. No running, playing, shouting, or anything else that would appeal to a young boy was allowed. (He came to regard Sundays in much the same manner he regarded the orange juice with which his mother mixed his castor oil. No small wonder that, as an adult with a choice, although he had deeply ingrained religious values and beliefs, he chose not to attend church until he had a child of his own who he was afraid was going to grow up a little “heathen.” He and Mother, whose family was Presbyterian, compromised: they became Episcopalians. It was a choice both of them were happy with, except that when it came time to repeat the words in the Nicene Creed, “I believe in the holy catholic church…,” my good Lutheran father just kept his mouth shut!)

Other days of the week were better for young Bubie. From his father he absorbed a love of the outdoors, which translated into many hunting and fishing trips. (Irma once told me that when he was very small, he couldn’t pronounce “fish,” but would get really excited when they were “gonna go catch some hih!”) Some of the snapshots saved from his boyhood show him with strings o f fish caught in the Cibolo, and later, strung-up deer beside a slender young man striking a “pose” with his rifle in one hand and the other on a cocked hip. He told me about his “Papa’s” favorite style of camp cooking: get a huge, two-inch-thick sirloin, lay it over the coals, and keep turning until black on the outside, done and juicy on the inside. His passion for hunting included chasing ‘coons all night with his friends Adolf and Henry Enck and their dogs, sometimes returning in the early hours with more than coonskins. An encounter with Brer Polecat resulted in having your clothes burned and your body scrubbed with lye soap until you were fit for human companionship again!

f fish caught in the Cibolo, and later, strung-up deer beside a slender young man striking a “pose” with his rifle in one hand and the other on a cocked hip. He told me about his “Papa’s” favorite style of camp cooking: get a huge, two-inch-thick sirloin, lay it over the coals, and keep turning until black on the outside, done and juicy on the inside. His passion for hunting included chasing ‘coons all night with his friends Adolf and Henry Enck and their dogs, sometimes returning in the early hours with more than coonskins. An encounter with Brer Polecat resulted in having your clothes burned and your body scrubbed with lye soap until you were fit for human companionship again!

In New Berlin, young George also found time to practice what would become an early source of accomplishment and pride: baseball. He would play by himself for hours, pitching a baseball against the side of the barn until he could hit the same spot over and over. He pitched for the Seguin High team, and for Billy Disch’s UT Longhorns for two years. During the summer of 1926 and ‘27, he came home to pitch for the Seguin White Sox, earning such comments from baseball writers as “arm of steel,” “pitched a whale of a game,” “bears down hard on the enemy,” “fertile material for the professional box.” For the seasons of 1928 through 1930 he signed on with the New Braunfels Tigers, where he rotated as pitcher with “Dazzling Dizzy” Dean. He also played alongside men with whom he would remain lifelong friends, including Ralph Stein, Buck Bergfeld, Red Schuenemann, Gilbert Staats, his brother-in-law Edgar Weyel and Edgar’s half-brother, Arlon Krueger. In one writeup from this period, he “averaged six strikeouts per game and has pitched ten games this season in which the opposition scored three runs or less, several of them being shutouts.” Not all his days on the mound were this good, but the many articles saved for him by his sister Irma in a scrapbook generally use glowing superlatives when they refer to his pitching performance. In 1931 he came home to re-sign with the Seguin club, and in 1932 he made the roster of the San Antonio Indians of the Texas League. He even got the chance to hurl against major league teams such as the Chicago White Sox and the Cleveland Indians when they made their exhibition tours. One of his fondest memories was having pitched three perfect innings against Cleveland. His baseball career seems to have ended with the 1932 season; no articles dated after that appear in the scrapbook. He was fiercely ambitious to get into the major leagues, but that didn’t happen. According to Mother, it was recurring attacks of the malaria he had contracted while playing in Louisiana that made it necessary for him to quit baseball. He, of course, disagreed; he never liked to admit that he was ill. I believe he considered giving in to illness to be a form of moral weakness. But several articles in the scrapbook from 1932 mention that he was removed from a game because of the heat, so I suspect that her version was accurate.

George had started school in New Berlin at the age of five. He attended the New Berlin school until he transferred to Seguin High School, from which he graduated in 1925 at the age of 16. That fall he entered the University of Texas, where he spent two years as a business major and member of the Longhorn baseball team. His father’s untimely death from a hunting accident in 1927 meant that he was needed to help in the family business, a store and cotton gin, which was heavily burdened with debt. He left school and returned to New Berlin to work beside his mother and sister, who were determined to keep the business running and pay off the vendors’ liens against the property.

At Seguin High, George had met Betty May Duggan, the daughter of a prominent Seguin family. Already an accomplished pianist under the tutelage of her aunt, Clara Madison of Houston, she followed George to the University in 1926 to major in music. Both left school in 1927 after O. J. Muelder’s death. They were married on December 20, 1928, at the Duggan residence (the “Old Short House”) in Seguin. The ceremony was attended by about fifty close friends and relatives. They honeymooned in New Orleans, afterward returning to Seguin to reside with Betty’s parents, Evelyn and Charles Duggan, in the Old Short House. During their early married life, there was little money, much of her family’s savings having been wiped out in 1929. But she shared his love of the outdoors, and they made trips to Port Aransas, camping on the beach and fishing in the surf. She also helped in the store occasionally, and taught music at their home in Seguin. George supplemented his business income by working as an oil leasing agent, driving all over South Texas to talk people into signing lease agreements. Later he did his own leasing and drilling, first in partnership with L. W. Campbell and then on his own.

They were both concerned about getting out of debt, and so postponed having children until that was accomplished. The store was a family operation. Blanche Muelder, who retained ownership until 1951 with her son as manager, worked in the store on a daily basis, and Irma Weyel helped frequently. As they grew up, Marjorie and Roger also worked in the business. Roger operated the gin’s elevator and seed crusher, getting his lungs well dusted in the days before people wore protective masks. By 1942 the liens were satisfied. But one morning in the spring of 1946, with a one-year-old child and just beginning to see their way out of the hole, George and Betty awoke to the devastating news that the store and family home had burned to the ground. Roger recalls that his father had roused him from bed because there were noises coming from the store. It sounded as if things were being thrown from the shelves, as someone would rifle through things hurriedly in a robbery. “Get your pants on!” cried Edgar, and father and son ran to the store with a shotgun, but saw flames licking out beneath the pier and beam structure of the building. Shortly thereafter the entire structure was ablaze. They had no hope of salvaging the store or anything in it. Because it had been a dry year, there was not enough water in the cistern to fight the fire. The house sat right next to the store and seemed certain to burn. They worked as fast as they could to empty all 16 rooms of the house. They managed to rescue the contents of all but two rooms, including a piano and the toilet (an unusual luxury in New Berlin at that time.) The heat was so intense that an Oldsmobile they had pushed away from the house had the paint burned off it on the side nearest the blazing structure. The fire department had not been called because the only phone was in the store. By the time word had reached Marion and the fire trucks neared at dawn, the store and house had burned virtually to the ground.

Glass bottles were melted into grotesque shapes by the intense heat. The safe could not be opened for about six weeks because exposure to oxygen would have caused the contents to ignite. With the home went much of the family’s irreplaceable memorabilia. The exact cause of the fire was never determined; however, because of the intense thunderstorm which had occurred that night, lightning was the primary suspect.

The old saloon, built in 1898 and located about fifty yards from the burned buildings, was the only usable structure spared. It was here, where George had been forbidden to enter as a boy, that Blanche Muelder and her son decided to set up business. The old building had covered over 5000 square feet; the saloon occupied less than 1000. In the warehouse, they housed feed, seed and implements. On the concrete porch at the back of the building would sit a big old-fashioned wooden icebox lined with tin. Because most country houses had the same kind of icebox to keep food, he sold about 500 pounds of ice every two or three days, hauling it from the ice house in Seguin in the bed of his pickup, covered with a heavy canvas tarp. The only electric refrigeration in the store at first was the meat counter; beer and sodas were kept cold with block ice in a Coke box on legs, and ice cream was preserved with dry ice (which also kept his little daughter entertained for hours on the back porch.) A large square metal drum fitted with a pump on top held kerosene, which powered lights and heat in many homes. A big commercial scale sat in the corner for weighing such items as sacks of pecans which he bought from people who had the trees.

The old saloon, built in 1898 and located about fifty yards from the burned buildings, was the only usable structure spared. It was here, where George had been forbidden to enter as a boy, that Blanche Muelder and her son decided to set up business. The old building had covered over 5000 square feet; the saloon occupied less than 1000. In the warehouse, they housed feed, seed and implements. On the concrete porch at the back of the building would sit a big old-fashioned wooden icebox lined with tin. Because most country houses had the same kind of icebox to keep food, he sold about 500 pounds of ice every two or three days, hauling it from the ice house in Seguin in the bed of his pickup, covered with a heavy canvas tarp. The only electric refrigeration in the store at first was the meat counter; beer and sodas were kept cold with block ice in a Coke box on legs, and ice cream was preserved with dry ice (which also kept his little daughter entertained for hours on the back porch.) A large square metal drum fitted with a pump on top held kerosene, which powered lights and heat in many homes. A big commercial scale sat in the corner for weighing such items as sacks of pecans which he bought from people who had the trees.

Inside, shelves lined the walls to hold everything from canned and boxed goods to nuts and bolts, tools, kitchenware, medicine and veterinary supplies, ammunition and fishing tackle, nails, you-name-it. If he didn’t have what you wanted in stock, he’d get it for you if he could. He bought eggs from local people, candling them one at a time during lulls in business. He also bought local produce, as well as meat and vegetables from vendors in Seguin and San Antonio. He ordered beef by the quarter, laying it out on the wooden counter atop butcher paper and carving it into steaks, roasts, ribs, and chops with a meat saw and a long butcher knife thinned in the middle from frequent sharpenings with the long steel. The scraps were ground into hamburger with a hand-cranked old-fashioned meat grinder. Using the same sharp knife that carved the meat, George could slice sausages and cheeses almost as accurately as any mechanical equipment. His thick-sliced bacon became a local legend; he even had a customer who came from San Antonio to buy it.

Inside, shelves lined the walls to hold everything from canned and boxed goods to nuts and bolts, tools, kitchenware, medicine and veterinary supplies, ammunition and fishing tackle, nails, you-name-it. If he didn’t have what you wanted in stock, he’d get it for you if he could. He bought eggs from local people, candling them one at a time during lulls in business. He also bought local produce, as well as meat and vegetables from vendors in Seguin and San Antonio. He ordered beef by the quarter, laying it out on the wooden counter atop butcher paper and carving it into steaks, roasts, ribs, and chops with a meat saw and a long butcher knife thinned in the middle from frequent sharpenings with the long steel. The scraps were ground into hamburger with a hand-cranked old-fashioned meat grinder. Using the same sharp knife that carved the meat, George could slice sausages and cheeses almost as accurately as any mechanical equipment. His thick-sliced bacon became a local legend; he even had a customer who came from San Antonio to buy it.

As I’m sure was true of the old Muelder Store, George’s place was far more than a place to buy staples and supplies. It was where people came at the end of a workday to visit and swap yarns, lies and jokes over a beer or two. It was where you came to find out what was going on in the community, to discuss crops and cattle, to have important papers notarized (George read every word of every document before he signed the notary’s affidavit), to pick up your mail if your box was one of those located in front of the store, to drop off mail for the RFD carrier if you weren’t on his route. If you were interested in the oil business, it was a place you could discuss core samples, underground formations, drilling, leasing, or the latest on whose well was producing what with George; a lifetime of chasing oil had given him a wealth of information, if not of “black gold.” It was, as the themesong for the TV show Cheers went, a place “where everybody knows your name.” If you’d ever been there before, George Muelder would remember you. He’d greet you with a smile and a handshake, and make you feel at home. He knew your kids, too, and would often give them a piece of candy or bubblegum from the old glass candy case beside the meat counter. Then they would probably notice one of the ever-present kittens that usually came into the world inside one of the large boxed rope coils in a darkish corner of the store. If George was lucky, some of those kittens would go home with some of those kids. Many, however, grew to cathood and stayed on, greeting him on the back porch each morning, sharing his lunch, napping in his lap, and eating the majority of the cat food he stocked. Dogs, too, found a home at Muelder Store, especially if they liked cat food. He never went for fancy names; they were “Gray Cat,” “Mama Cat,” “Old Yeller Cat,” “Little Puppy.” His favorite stray dog, though, did get a name: Brownie.

As I’m sure was true of the old Muelder Store, George’s place was far more than a place to buy staples and supplies. It was where people came at the end of a workday to visit and swap yarns, lies and jokes over a beer or two. It was where you came to find out what was going on in the community, to discuss crops and cattle, to have important papers notarized (George read every word of every document before he signed the notary’s affidavit), to pick up your mail if your box was one of those located in front of the store, to drop off mail for the RFD carrier if you weren’t on his route. If you were interested in the oil business, it was a place you could discuss core samples, underground formations, drilling, leasing, or the latest on whose well was producing what with George; a lifetime of chasing oil had given him a wealth of information, if not of “black gold.” It was, as the themesong for the TV show Cheers went, a place “where everybody knows your name.” If you’d ever been there before, George Muelder would remember you. He’d greet you with a smile and a handshake, and make you feel at home. He knew your kids, too, and would often give them a piece of candy or bubblegum from the old glass candy case beside the meat counter. Then they would probably notice one of the ever-present kittens that usually came into the world inside one of the large boxed rope coils in a darkish corner of the store. If George was lucky, some of those kittens would go home with some of those kids. Many, however, grew to cathood and stayed on, greeting him on the back porch each morning, sharing his lunch, napping in his lap, and eating the majority of the cat food he stocked. Dogs, too, found a home at Muelder Store, especially if they liked cat food. He never went for fancy names; they were “Gray Cat,” “Mama Cat,” “Old Yeller Cat,” “Little Puppy.” His favorite stray dog, though, did get a name: Brownie.

During his years as a storekeeper, George also farmed and raised cattle on the 217 acres that made up the old Muelder farm, purchased by his father in 1910, about a quarter of a mile down the road from the store, as well as the 98 acres that made up his 1952 purchase from R.E. Tewes across the road. George had the land terraced and fenced, and over the years, by purchasing good bulls, bred up a bunch of mixed cattle into a herd of first-class Herefords that he delighted in looking at and hand-feeding. He didn’t believe in horses, but rounded up his cows by leading them into the pen with his pickup loaded with hay bales and a sack of range cubes. He stopped branding them because he thought it was cruel. He never enjoyed selling his cattle, and as he got older, he even refused to butcher his own calves for beef. They became more like pets, and he was happy if the farm broke even.

His love of nature and animals manifested itself on the farm in many ways. Although he planted many crops, from cotton, peanuts, corn, clover, oats and sudan to truck garden vegetables, he made sure to keep part of it in wild pasture land, with plenty of trees and brush for wildlife and for the cattle to use as protection from the weather. He enjoyed the wildflowers that grew up in the coastal fields; we often didn’t shred until they had gone to seed. On Sunday mornings he and I would often walk over the fields, stopping to pick up a handful of soil and run it through our fingers, or follow a cattle trail back into the thick brush of the pasture. We might spend an hour or two casting into the tank for the bass he had stocked there, but usually “patted ‘em on the head” and put them back. We had lots of jackrabbits, coyotes, rattlesnakes, birds, squirrels, and even a few deer in the back 40. We hunted doves in the fall, but he insisted that most of the animals be left in peace, even the snakes. He was careful to teach me the difference between poisonous and non-poisonous varieties, because he recognized that the “good” snakes, such as bull snakes, king snakes, coachwhips and chicken snakes, held down the rodent population as well as keeping the “bad” snakes in check. One morning we were driving down a track on the farm when he stopped the truck and told me to look where he pointed. There, halfway out of a hole, was a bull snake in the process of swallowing a small rattler. It was a lesson I never forgot.

After his father’s death in a hunting accident, George had promised himself that when he had children of his own, he would quit deer hunting, and he kept that promise. But he never lost the thrill of the chase; he only translated it into fishing. With his friend Louis Brenner, and later Ben Stein and/or me, he would leave the house around four AM most Sunday mornings, and usually return around eight, smelling of fresh fish and cigars, with a respectable string of bass, catfish, crappie, or perch. Our regular Monday night meal was one of the above, fried in cornmeal and accompanied by French fries and coleslaw. He did not believe in “trophy hunting;” there were no mounted fish on our walls. But as long as you could eat it, go for it! There was one exception to this rule. One Sunday he brought home an eight-pound bass that he had enticed from under a willow tree on the Guadalupe. That was the lunker of his fishing career. Instead of being filleted for the table, it stayed whole in the freezer for at least a year, where visitors could appreciate its length and girth. After it had been appreciated by all, it was too far gone to eat. Another Sunday morning I heard a gasp from the bathroom. Mother had turned on the light only to discover that the bathtub was occupied by a 27-lb yellow catfish. He wanted us to see that one, too. When I “helped” him clean it (I was about three) we discovered that it had just swallowed a baby squirrel. I remember refusing to eat any of that “bad” fish! One more fish story: when I was a child, Daddy’s idea of a long vacation trip was to get up at two AM, drive to Rockport or Port Aransas, go out with a guide in the morning, and return to Seguin that afternoon, stopping only to pour the water off the garbage cans in the trunk, which were full of melting ice and trout, mackerel or kingfish. That way he saved the price of a motel and an icechest, and we had fish for the rest of the year. But even “Generous George” had his limits. He told about a trip with his father before anyone had refrigeration. They caught a truckload of mackerel, and after giving away all they could, they ate mackerel three meals a day for a week. He said it was a long time before he could even think about eating another mackerel!

My dad was also a fairly accurate weather forecaster. If you walked into the store and said, “Well, George, is it going to rain today?” you could usually bet on his response. He could look at the clouds in the evening, or the way the birds and animals acted, and tell what the next day’s chances would be. Like all farmers, he loved rain, but when drought came in the 50’s and he watched even the mesquite brush die and the topsoil blow away, he didn’t quit farming. He sold down to eleven head of cattle, fed them the hay he had stockpiled, and hung on until conditions improved. Being prepared, “saving up for a rainy day” were part of his working philosophy. He worked on through extremes of heat and cold, even after his health began to falter and he would get dizzy or sick. The weather was just part of life that you accepted because you had to, not something to “bellyache” about.

Despite chronic heart failure, two abdominal surgeries, a bad back, painful feet, deafness and bouts of depression, Daddy continued to keep his store open six days a week, twelve to fourteen hours a day, until he was 81 and suffering from confusion and memory loss in addition to his other ills. It became a place of refuge for him as well as others; here he could relax, laugh, drink a few beers, pitch some washers with the fellows behind the store, and reminisce with the many friends who dropped in more for the company they would find than to purchase groceries, many of which had long outlived their “sell by” dates on the shelf. The dust grew thick, as did the cobwebs, for Daddy didn’t believe in killing spiders (or in too much dusting, for that matter; he said it would “ruin the atmosphere.”) He allowed the yellow jackets to nest under the porch roof, and a swarm of bees to build their hive between the walls of the store. The paint peeled, but that “just adds to the atmosphere.” The building’s foundation settled, causing the floor to buckle and the shelves to sag, but he just said, “That’s all right. It’ll last as long as I will.” In 1992, finally unable to drive or to stand behind the counter, he fulfilled an old handshake agreement by selling the store to his neighbor, John Bohannon. When the building was torn down shortly thereafter, I drove him out to New Berlin, fearful of his reaction. His only comment was, “Well, it looks better now.” He lived at home in Seguin until, after a short stay in a nursing home, he died on August 23, 1995.

depression, Daddy continued to keep his store open six days a week, twelve to fourteen hours a day, until he was 81 and suffering from confusion and memory loss in addition to his other ills. It became a place of refuge for him as well as others; here he could relax, laugh, drink a few beers, pitch some washers with the fellows behind the store, and reminisce with the many friends who dropped in more for the company they would find than to purchase groceries, many of which had long outlived their “sell by” dates on the shelf. The dust grew thick, as did the cobwebs, for Daddy didn’t believe in killing spiders (or in too much dusting, for that matter; he said it would “ruin the atmosphere.”) He allowed the yellow jackets to nest under the porch roof, and a swarm of bees to build their hive between the walls of the store. The paint peeled, but that “just adds to the atmosphere.” The building’s foundation settled, causing the floor to buckle and the shelves to sag, but he just said, “That’s all right. It’ll last as long as I will.” In 1992, finally unable to drive or to stand behind the counter, he fulfilled an old handshake agreement by selling the store to his neighbor, John Bohannon. When the building was torn down shortly thereafter, I drove him out to New Berlin, fearful of his reaction. His only comment was, “Well, it looks better now.” He lived at home in Seguin until, after a short stay in a nursing home, he died on August 23, 1995.

Several incidents during his later years illustrate the esteem in which George was held by his friends at New Berlin. For both his eightieth and eighty-first birthdays, they threw barbecue parties behind the store, complete with cake, presents and washer contests. Freddie Frederick, as Mayor, presented him a Certificate of Appreciation, and the year after his death, he was selected by the City Council as Man of the Year. Because he never bragged about such things, I will never know the full extent of the generosity for which he was famous (an old friend, Elam Scull of La Vernia, once told me, “Your Daddy would have owned an H.E.B. by now if he hadn’t given half of it away”). But I will always remember, with respect and not a little awe, the absolute honesty, integrity and decency with which he conducted both his business and personal life. Not to speak of the fun we had, and the father I loved, learned from, and will always miss. I also remember that, even though he didn’t make his family home in New Berlin, he was intimately involved with the life of the community, giving his time and services to projects such as the annual sausage supper as well as to individuals who happened to need help. Perhaps my father never made the major leagues in baseball or in the business world, but to me he was the most successful of men: one whose legacy was to leave all of us better for having known him. If it is true that “a rich person is not the one who has the most, but is one who needs the least,” then George Muelder was a rich man indeed.

THE SCHULTZE’S IN NEW BERLIN

submitted by Dawn Young

They came. They stayed. What more can be said?

Johann Heinrich Schultze (hereafter referred to as Johann Heinrich I) came to America in 1844 on the ship “Johann Dethardt” with his wife and two children. They arrived in New Braunfels, Texas in 1845. They made their home six miles South of New Braunfels. His brother, Friedrich Heinrich Herman Schultze made his home about two miles North of New Berlin in Guadalupe County, Texas. It is not totally clear whether Johann and Friederich are brothers or cousins, but until other proof can be obtained, it is assumed they are brothers.

Johann Heinrich I was born on January 3, 1811 in Nettin on the Berg, Province of Verden on the Aller, Hannover, Germany. His wife, Katharine Adelheid Uelzen/Oelstein was born in Arnsen, Province of Verden on the Aller, Hannover, Germany. They were married in 1837, in Germany. They had the following children: Herman, born 09-10-1838, in Armsen, Germany; Friedrich, born 09-22-1841; Sophie born 11-08 or 09-1848 (Sophie married Johann Heinrich Schultze II); and Wilhelmine, born 03-27-1851 (Wilhelmine married Herman Schultze). (Johann Heinrich II and Herman Schultze were brothers and were the sons of Friederich and Anna Maria Lindhorst.) Johann Heinrich I died December 1, 1889, and is buried in the New Braunfels City Cemetery. His wife Katharine (also known as Catharina Adele) is buried in the Schultze Family Cemetery, New Berlin. She died on March 4, 1885.

Friederich was born on April 28, 1819, in Hohen Auf-em Berge, Germany. His wife, Anna Maria Lindhorst, was born February 28, 1821, in Arnsen at Verden, Hannover, Germany. She died on September 23, 1900, in Guadalupe County, Texas. He died on November 9, 1888, in Guadalupe County, Texas. Both are buried in the Schultze Cemetery about one mile north of New Berlin. The property is currenly owned by Schultze descendant, Marietta Gerhart. Friederich and Anna had the following children, Johann Heinrich II (married Sophie Schultze, mentioned above); Herman (married Wilhelmina Schultze, mentioned above), Margarethe; Fritz; and Diedrich.

As you can see, things get a little complicated. If, as is believed, Johann Heinrich Schultze I and Friederich Schultze were brothers, then Johann’s daughters married Friederich’s sons.

Why did Sophie and Wilhelmina marry their cousins? Had the family lost contact with one another? Johann Heinrich I came to America in 1844. It is unknown when Friederich came to America, but his son Johann Heinrich II built his home in New Berlin after 1870. Johann Heinrich I’s youngest son, Diedrich, was born in Germany in 1860. Apparently he came over sometime in between.

Nevertheless, they came. Johann Heinrich I was a founding colonist of New Braunfels, receiving Lot # 54 containing about 1/2 acre Bavarian measurements. It was sold to him by the German Emigration Company with acting Trustee named Herman Spiess. The land is situated in the City of New Braunfels. His nephew, Johann Heinrich II built a two story house north of Marion, in 1870. In 1894 he built a large rock house about ¾ mile north of New Berlin. There he had a large vinyard which he had set up with irrigation. This is the same property on which the Schultze Family Cemetery is located.

Many Schultze descdants still live in the immediate New Berlin area. Among them are Roma Schultze Lenz. Roma’s father, Edward Schultze, was known as Butcher Schultze, as he was the local meat cutter. He followed in his father Diedrich’s footsteps, as he was also a local butcher. Diedrich and his wife, Maria Wieters, made their home on Linne Road about one mile North of New Berlin. Diedrich was the son of Friedrich and Anna Schultze.

Other Schultze descendants still living on or near the original Schultze farms are Bill Schultze, Scott Schultze, Joyce Schultze Young and Morris Vader, and the Marietta Gerhart Family.

Many of the Schultze’s are buried in the Schultze Family Cemetery, which is located on the Gerhart Farm. They are Catharina Adele Schultze; Frederick Herman Henrick Schultze and Anna Maria Schultze; Heinrich John Schultze and Sophia Schultze; Henrich Schultze and Thelka Schultze; Viola Schultze; Fritz, Emil, Herman Friederich and Herman Heinrich (children of Heinrich & Sophia); Herman and Wilhelmina Schultze. Some of the names of these individuals were “Americanized” and are spelled a little differently on their tombstones than they are listed elsewhere in this article.

There are more questions than answers when studying the Schultze Family. If you know of information about the Schultze’s in New Berlin, or if the information presented is incorrect, please contact Dawn Young.

Johann’s wife – Sophie Schultze Born 11-8 or 11-9-1848, in the Santa

Clara community. They were married on 5-26-1872. She died on 12-18-

1929 and is buried in the Schultze Cemetery. Her father is believed to be a

brother to her husband’s father.

The information in this article was taken from the Schultze Family Book which provides information on the descendants of Georg Hinrich Schultze from 1740-1992.

Friedrich Herman Heinrich Schultze

Born 4-28-1819, In Hohen-auf-em Berg, Germany

Died 11-9-1888; Buried in Schultze Cemetery

Wife – Anna Marie Lindhorst

born 2-28-1821 or 1828 in Armsen, at Verden, Germany Died 9-23-1900; Buried in Schultze Cemetery

Children-Johann Heinrich Schultze, born 7-25-1844, in Armsen, Verden, Hannover, Germany

Founding Family-The Tewes Family

by Kathy Hale

Carl August Edward “Ed” Tewes had a great impact on the settlement and founding of the German community of New Berlin. He made significant contributions in education, commerce and government service.

Ed Tewes was born in Furstenberg, Waldeck, Province of Hessen, Germany on March 16, 1842. He immigrated to Texas at the age of twelve with his mother Christiana Emden Tewes, age 44; his brother Louis, age 8; and half-sisters, Auguste, age 18 and Marie, age 16. They came to America on the U.S.S. Minerva, which landed at fort New Orleans, Louisiana on June 26, 1854.

Ed Tewes was born in Furstenberg, Waldeck, Province of Hessen, Germany on March 16, 1842. He immigrated to Texas at the age of twelve with his mother Christiana Emden Tewes, age 44; his brother Louis, age 8; and half-sisters, Auguste, age 18 and Marie, age 16. They came to America on the U.S.S. Minerva, which landed at fort New Orleans, Louisiana on June 26, 1854.

As had most of the German immigrants who settled in Central Texas, the family took a ship to Galveston and then a smaller boat to Indianola, Texas. Then they went by stagecoach to New Braunfels to join the father and older brother. His father, Louis Johann Christian Ludwig Tewes, had previously immigrated to Texas with his eldest son, William, on the ship Colchi in 1846. They had been in Texas eight years prior to the arrival of the rest of the family.

Within a year (1854), Ed’s mother died, probably of the dysentery epidemic of that time. She was buried at Yorktown. A year later (1855), Ed and his father were ambushed by Commanches between the Cibolo Creek and San Antonio. Ed hid in a mesquite thicket and saved himself, but his father was scalped. Ed took his father’s body to Lindeneau in a wagon (a 3 day journey) and buried him. He and his brother, Louis, were orphaned. Ed’s half-sister Auguste, by then married, took Ed into her home. His other half-sister, Mattie, took Louis.

Ed Tewes served in the Civil War for three years as a Confederate soldier. He was a member of Company One of the Third Texas Volunteers. He joined the regiment in San Antonio; the headquarters then were located where the Gunter Hotel now stands. As a member of the unit, he marched from San Antonio to Fort Ringold, Fort Brown, Fort Davis, and from there to Arkansas and on to Louisiana.

After the war he returned to New Berlin and began building his sizable business holdings.

His first store was so small it was called the Speckbox. Later, a larger store and dance hall were built. He was a self-made man and his wealth and influence in the New Berlin area can be clearly traced through records of his transactions at the Guadalupe County Courthouse, Seguin, Texas.

The first recorded deed involving Edward Tewes was recorded in August of 1867, when he was granted a mortgage by J.J. Dunn for horses and mules for his stables.

In 1870 he purchased 137 acres on the Cibolo Creek from Rudolph Hellman. Family history indicated that the house was built prior to Tewes’ marriage to Texanna Wooten Newton of Guadalupe County in 1876. Four children were born in the house: Annie, 1877; Walter Edward, 1878; Mary Auguste, 1879; Robert Emden, 1880.

As one of the original settlers, Tewes was instrumental in founding the town of New Berlin in 1868. Over the course of the next 15 years, he amassed 1,356 acres in and around the town of New Berlin. He established three general stores: one in New Berlin, one in LaVernia, and one in Karnes City. “In the Beginning: A History of Marion”, indicates that after 1883, Tewes also had a store in Marion.

He was appointed Postmaster of New Berlin on April 1, 1878 and held this position for 26 consecutive years.

In 1891, he and several others petitioned the county to organize a school community at New Berlin. The petition was granted; New Berlin School Community #53 was established and the school was built on land donated by Tewes. Tewes was appointed as a trustee and served as such until he moved to San Antonio in 1894. His photo still hangs inside the school, which is now the Community Center of New Berlin.

In 1894, Ed and Texanna Tewes moved with their children to the King William District of San Antonio. They kept the house in New Berlin. Emil Brietzke occupied the house and ran the store at New Berlin, but Tewes retained the room in the rear of the house for Mr. Tewes when he came to New Berlin to check the store.

Ed Tewes died in December of 1936, leaving the ‘country home’ at New Berlin to his son Walter, who had been born in what is now the kitchen of the house in 1878. He and his wife, Elsie Clara Wagner Tewes, owned and occupied the house for the remainder of their lives. After their deaths, the house was sold. It had been in the Tewes family for one hundred years.

Additionally, the house is architecturally significant because it exemplifies early Texas pioneer techniques using indigenous materials. It has been completely restored by the current owners, Mike and Kathy Hale following the guidelines for historic restoration.

The house received Texas Historic Landmark designation in 1996 from the Texas Historical Commission and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 9, 1997.

THE WARNCKES OF NEW BERLIN

Heinrich Sr. and Elisabeth Eitzman Warncke of Wittorf Germany came to America in 1868 under the auspicies of the the Evangelical Church of Visselhoevede, Hannover. On the 1st of May 1868, Heinrich, 29, and Flisabeth 25, along with their two Small children, Maria, 2 1/2, and Heinrich Jr., 18 months, sailed out of Bremen, Germany on the SS Baltimore. Eighteen days later, on May 19 they landed in Baltimore Harbor, Maryland. From there they went to Napoleon, Henry County, Ohio where they lived until 1874. At that time they came by train to settle in New Berlin, Texas. Elisabeth’s brother, Herman Eitzman, came with them but soon returned to Ohio.

Upon their arrival in New Berlin, the family stayed with the Herman Schultze family for approximately two years. Two of Heinrich’s brothers, Fritz and Wilhelm, who came to the U.S. by way of New York on August 10, 1869, also lived in the area. Heinrich and Elisabeth purchased 172 acres of land about two miles south of New Berlin from Ed Tewes July 26, 1876. The purchase price was $1141.65 @ 12% interest and was paid off on January 1, 1878. An adjacent 220 3/4 acres were purchased in May 1882 from John Smith et al for $883.00 cash. The Warncke cattle brand was registered in the Guadalupe County Courthouse on February 26, 1876. Working side by side, the couple cleared the land for farming, hand dug a well, built a house, and set about the business of raising crops, poultry, livestock, and whatever else it took to sustain their ever growing family. Produce and other farm goods were taken by wagon to San Antonio and sold at the market.

The pair had thirteen children in the years 1864-1889. Elisabeth was twenty years old when she had the first and forty-five the last. It is said that Heinrich Sr. acted as midwife. Maria and Heinrich Jr. were born in Germany. Sophie, Kate, Anna and one unidentified child were born in Henry County, Ohio. Minna, Mathilda, Willie, Fritz, Lillie, Louisa, and Adele were born in Texas. The unidentified child is buried in Henry County, Ohio. Anna died in Bexar County on January 18, 1875 and was buried January 20 in the New Braunfels Cemetery, “# 30, in the four bit section, fee paid to Sextant Kelner.” The eleven surviving children all married, except Sophie. They produced 59 grandchildren and 133 great grandchildren. There are seven generations in 2001.

Despite the language barrier, they were well established and respected in the community. They were members of Jaegerlust Shooting and Bowling Club, subscribed to the German language newspaper, Die Braunfelser Zeitung, educated their children, and were active in community affairs. Daughter Kate Penshorn was appointed to the New Berlin School Board of Trustees in 1921, the first of three females to hold that position. Two sons-in-law, Gus Penshorn and Emil Penshorn Sr. served as trustees, as did grandson Alfred Warncke Sr.

Determined to go to church they became members at Comaltown Church in New Braunfels, a wagon ride of about twenty miles over rough terrain and low water crossings. When Comaltown Church disbanded, they attended First Protestant Church also in New Braunfels. In 1900 Redeemer Church in Zuehl was established and Elisabeth joined that church where she remained a member until her death in 1921.

A portion of the homestead was set aside for a family cemetery. The first marked grave is that of Anna Helmke, born August28, 1879 and died December 2, 1880.

Heinrich Sr. was born March 11, 1839. He died March 19, 1908, in his home of la grippe and circulatory disease at the age of 69 years and 8 days. According to his death record, he was a citizen. His occupation was farmer. As was the custom, his casket was set up in the parlor of their home and large blocks of ice were set underneath. Many bouquets of red roses and other flowers were placed all around the casket. Otto Muelder, the storekeeper, was the undertaker. Pastor Knicker of Redeemer Church conducted the services. His Bible verses were John 5 24-27 and John 5. 40. He was buried in the Warncke Cemetery.

Upon his death, Elisabeth was named heir and executrix of the joint will they had made in 1898. In 1909, Elisabeth made a new will naming her children as heirs. She made a special provision for “Sophie, my afflicted daughter” (Sophie suffered with epilepsy). She remained on the homestead until about 1918-19 when bad health caused her to move in with various of her children. Elisabeth, daughter of C. H. Eitzman and ? Koenfeldt Eitzman, was born in Ottingen, Rotenburg on the Wumme River, Hannover, Lower Saxony Germany, November 26, 1844 and died December 31, 1921 at the home of her daughter and son-in-law Louisa and Erich Bloch. She was 77 years old, cause of death listed as stomach cancer. Otto Muelder was undertaker. Her doctor was M.B. Brandenberger. She was a shareholder in the LaVernia Farmers Gin Co. and had made loans to various people, including business owners at a rate of 6% interest. Her obituary gives a glowing account of her kindness and position in the community and makes reference to the large attendance and many flowers at her funeral. Pastor Knicker conducted the services at Zuehl Redeemer Church on January 2, 1922. Her Bible verses were Romans 8: 11 and John 5: 24-25. She was buried next to her husband in the Warncke Cemetery.

Stories handed down through the generations give insight to the personalities of this family. One can only imagine the determination these people had. The decision to come to a “foreign land” must have been difficult. Would they ever see the family and homeland they left behind? How would the climate and living conditions compare? It is told that Elisabeth was teased because she brought her ice skates to hot, humid South Texas. The winter of 1886 was one of the coldest on record, and Elisabeth skated on the frozen stock tank. She would have been in her early 40’s. Heinrich Sr. enjoyed German march music and played the phonograph loud enough for the neighbors to hear. This usually happened on Sunday mornings. He also frequented Muelder’s Saloon. In later years when Elisabeth would leave on her Sunday afternoon visits, the teenage grandchildren would sneak into her parlor and play that phonograph and dance. They said Grandma always pretended not to notice the mess they left behind. This remarkable woman had thirteen children in twenty-five years, endured the death of two small children and a grown daughter, to say nothing of hardships she must have faced and conquered. She also took care of and tended to Sophie’s needs at a time when not much was known about epilepsy.

Many discrepancies and questions arise when doing research. Among them is the question of Sophie’s birthdate. Her tombstone reads 1868, but her baptism record in Henry Co. Ohio shows she was born in Ohio in 1869. That is logical since the ship’s list does not list her as a passenger, and all passengers were listed no matter the age. The other puzzle is who was Anna Helmke? Anna Helmke’s parents were Dietrich and Maria Mahlman Helmke. Maria’s parents were Herman and Anna Katherine Maria Warncke Mahlman. Anna Helmke was the granddaughter of Anna Katherine Maria Warncke Mahlman. Was Anna Katherine Maria Warncke Mahlman the sister of Heinrich, Sr.? Another question is who are in the unmarked graves in the Warncke Cemetery? This is an on going project and much is yet to be found. Not too much is known about the years in Ohio.

In 1976 the homestead was registered with the Family Land Heritage Program sponsored by the Texas Department of Agriculture, signifying that for at least 100 years part of the acreage is still owned and operated as a working farm and ranch by descendants of the original owners. Great granddaughter Marlene Warncke Young and husband Wilbert Young are owners and operators of this land located on Warncke Road.

The Warncke Cemetery was registered as a Historic Texas Cemetery by the Texas Historical Commission in 2001 and a marker was erected on the site located on Warncke Road, 1.2 miles from the intersection of FM 775 and Warncke Road. The cemetery contains twenty-seven marked graves and five unmarked graves, as well as a memorial marker for a grandson of Heinrich Sr. and Elisabeth, PFC Elmer G. Bloch. He was killed in World War II in Tunisia and his body could not be returned to the United States for burial. He is interred in Beja, Tunisia. The earliest marked burial was 1880 and the last burial was in 2000. This cemetery has been well maintained through the years by descendants. The original picket fence that surrounded the cemetery was replaced by a cyclone fence. The crepe myrtle trees planted on the grounds are well over fifty years old. Ancient oak trees stand tall on the site. Wildflowers cover the grounds in the springtime.

In the year 2001 the family tree branches into many business and professional fields, continues to grow and flourish, and stands proudly in tribute to Heinrich and Elisabeth whose desire for a better way of life began one hundred thirty-three years ago. Direct descendants and their families who still live in the New Berlin area include Shirley Baumann; Bobby, Jerry, and Rodney Brietzke; Betty Doege; Frank Doege Jr.; Jimmie Penshorn; Lula Bell Rakowitz; Carolyn Schultze; Dorothy Mae Vader; Janie Wallace; Irene Wiedner; Mark Williams; and Marlene Young.

Written by Vivian Warncke McKee

The Zuehl Family

By Robert & Billie Zuehl